a/n: A quick note. For more in-depth information, see ultracold atoms.

A state of matter. In sci-fi movies, BECs froze many people to death. In reality, they must be well isolated from the environment using vacuum technology, kept in the dark and in non-magnetic containers to prevent it from heating up. In fact, their heat capacity is so low that you couldn’t even cool a small grain of sand with it, not to mention a whole person! Also, the condensate usually only lasts for a few seconds.

Conditions for Formation: video

-

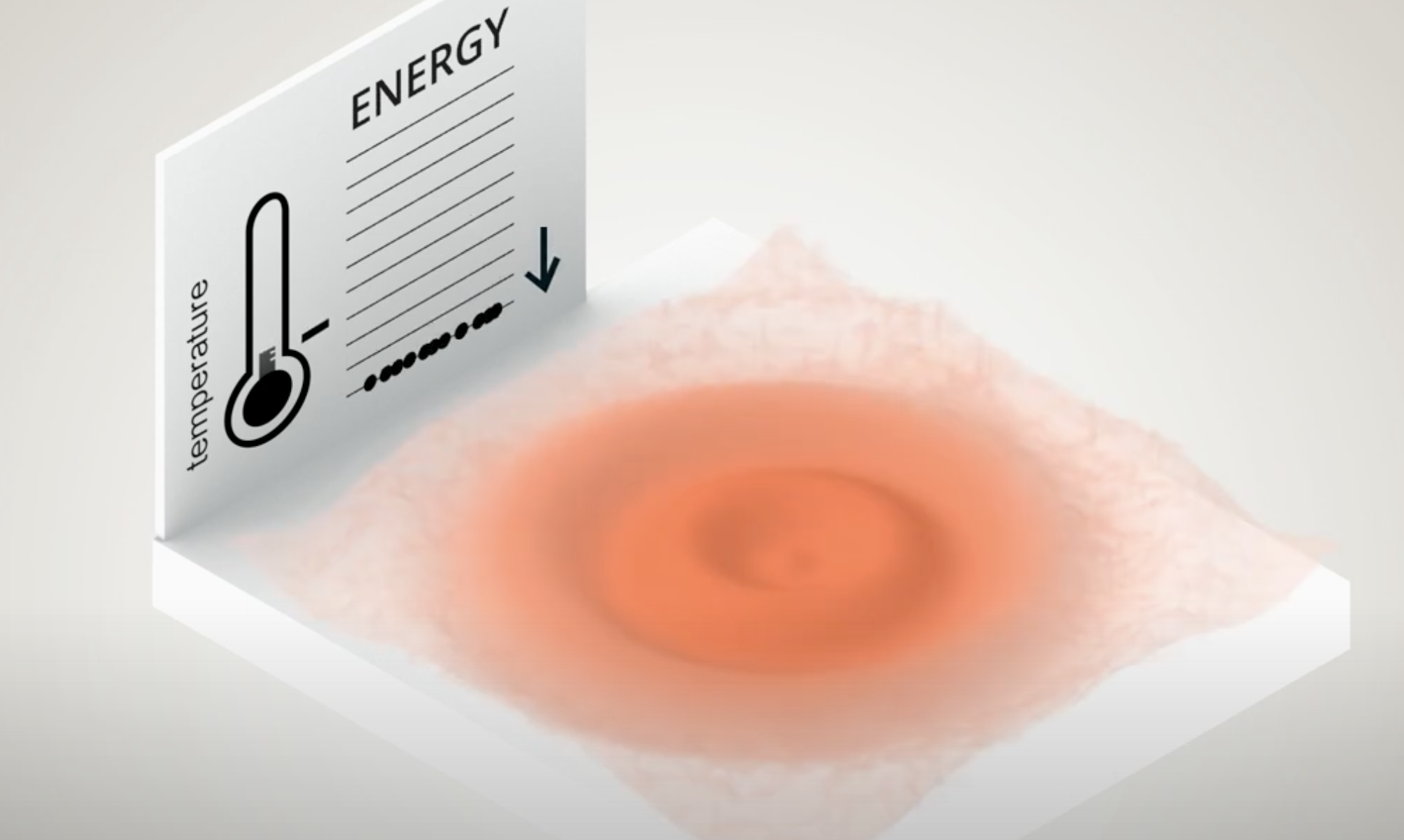

Given density and extremely low temperature:

Achieved in labs using cooling techniques like laser cooling and evaporative cooling. At a fixed density, lowering the temperature reduces the thermal energy of the articles, allowing them to settle into the lowest possible energy state. These atoms’ wavelengths will expand and will reach a collective quantum state, called the Bose-Einstein condensate. Temperature drops below a critical threshold/Bose-Einstein condensation temperature. -

High density for a given temperature.

For a fixed temperature, increasing the density of particles increases the likelihood of them occupying the same quantum state. In extreme environments like neutron stars, the density is so high that particles are forced into overlapping quantum states, even at relatively high temperatures. However, in lab conditions, achieving such high densities is impractical because it leads to strong interactions that disrupt the condensate. Instead, labs focus on low temperatures to achieve BEC.

Particle Types. Everything is either a boson or a fermion. The spin of an object determines whether it is a boson or a fermion.

- Bosons: Can overlap and occupy the same quantum state (e.g., photons, helium-4 atoms).

- Fermions: Cannot overlap due to the Pauli exclusion principle (e.g., electrons, protons).

- Fermions can form BEC-like states only when they pair up to act as composite bosons (e.g., Cooper pairs in superconductors).

Laser Cooling:

Atoms floating in space have specific absorption wavelengths corresponding to their electronic transitions. To cool them, a laser with a slightly longer wavelength is used. When atoms move toward the laser, they perceive the laser photons as blueshifted due to the Doppler effect (3.1). This allows the atoms to absorb the photons (3.2), with momentum opposite to the atom’s direction and hence slowing the atom down. Repeat ad nauseum. After absorption, the atoms emit photons in random directions (3.3). Once the atoms stop moving, they no longer absorb photons, allowing them to accumulate in the center. This process is like a physical implementation of an “if statement”—if the atom is moving toward the laser, it absorbs photons and slows down; else, it remains unaffected. Isn’t that neat?

Atoms floating in space have specific absorption wavelengths corresponding to their electronic transitions. To cool them, a laser with a slightly longer wavelength is used. When atoms move toward the laser, they perceive the laser photons as blueshifted due to the Doppler effect (3.1). This allows the atoms to absorb the photons (3.2), with momentum opposite to the atom’s direction and hence slowing the atom down. Repeat ad nauseum. After absorption, the atoms emit photons in random directions (3.3). Once the atoms stop moving, they no longer absorb photons, allowing them to accumulate in the center. This process is like a physical implementation of an “if statement”—if the atom is moving toward the laser, it absorbs photons and slows down; else, it remains unaffected. Isn’t that neat?

Lifetime in Labs:

BECs are typically very diluted gases (1/100,000 of normal air density). They last only a few seconds in lab conditions due to interactions with the environment.

Visibility:

BECs do not scatter light visibly, but their wave-like nature can be observed using specialized imaging techniques.

Zero Resistance and Movement:

In a BEC, particles occupy the same quantum state, leading to macroscopic quantum phenomena. Resistance can be zero because all particles move coherently without scattering off each other.

States of matter are defined by properties like conductivity, density, and quantum behavior.

A play to illustrate BECs - Source

The scene takes place on a sidewalk on 5th Avenue in New York City. A man named Dr. Bose is sitting behind a card table. On the table are some cups, balls, tape, paper and a black felt-tipped pen.

[A tourist comes up to Dr. Bose’s table.]

Dr. Bose: “My name is Satyendra Nath Bose. Would you like to play Monte?”

Tourist: “How do you play Monte?”

Dr. Bose: “Well, normally a ball is placed under one of three cups. Then I shuffle the cups quickly hoping to confuse you. You guess which cup contains the ball. If you are correct, I give you a dollar. If you are wrong, you give me a dollar. Sounds simple, no?”

Tourist: “I have keen eyesight. Let’s play.”

Dr. Bose: “Well, eyesight won’t help you with my version of Monte. In my version of the game, numerical labels – one, two and three – are taped to three balls. You get to put the three balls under the cups. Then, you get to guess which number is under a particular cup. During this whole process, I don’t touch anything – not the balls, not the cups. Only you handle them. Sounds like an easy way to make a buck, doesn’t it? Want to play?”

Tourist: “Are you a magician?”

Dr. Bose: “No, I am a physicist.”

Tourist: “Well, in that case, let’s play.”

Dr. Bose: “Here are the balls, here is some tape, here are the labels and here are the cups.”

[The tourist takes that three balls and attaches labels with the numbers one, two and three to the balls. He then places the number one ball under the left cup, the number two ball under the middle cup and the number three ball under the right cup.]

Tourist: “Now what?”

Dr. Bose: “Choose a cup.”

Tourist: “The middle one.”

Dr. Bose: “Tell me what number is under it?”

Tourist: “Two.”

Dr. Bose: “O.K. Lift up the middle cup.”

[The tourist lifts the middle cup and is astonished to find the ball with the label one under it.]

Tourist: “That’s impossible. I’m sure that I put the number two ball under the middle cup.”

[The tourist hands Dr. Bose a dollar.]

Tourist: “Let’s play again.”

Dr. Bose: “O.K. Put the number one ball back under the middle cup.”

Tourist: “Done.”

Dr. Bose: “Choose a cup.”

Tourist: “The middle one.”

Dr. Bose: “Tell me what number is under it?”

Tourist: “One.”

Dr. Bose: “O.K. Lift up the middle cup.”

[The tourist lifts the middle cup and indeed finds the ball with the label one is under it.]

Tourist: “Give me back my buck.”

[Dr. Bose returns the dollar.]

Tourist: “I must have just made a silly mistake the first time.”

[The tourist puts the number one ball back under the middle cup.]

Tourist: “I again choose the middle cup and ball number one will be under it.”

[The tourist lifts up the middle cup only to find the number two ball under it.]

Tourist: “That’s strange. The number two ball was the one I originally thought was under the middle cup.”

[The tourist gives a dollar to Dr. Bose.]

Tourist: “Well, since we’re back to the original situation. The number one ball is probably under the left cup.”

[The tourist picks up the left cup, only to find that the number three ball is under it.]

Dr. Bose: “You lose again.”

Tourist: “I thought you said that you were not a magician.”

Dr. Bose: “I’m not.”

Tourist: “Then how did you do this trick?”

Dr. Bose: “It is not a trick and I did not do it. It did it itself.”

Tourist: “I don’t’ follow.”

Dr. Bose: “These three balls are bosons and they are part of a Bose-Einstein condensate. Their individual wave functions do not exist. Instead, they have a collective wave function, which does not permit them to be distinguishable. Thus, when you lift a cup, it is equally probable that you will pick any numbered ball. That is why I do not have to touch the cups. The balls randomize themselves automatically.”

Tourist: “I didn’t understand a word you said. Hey, I know what you are. You’re one of those . . . What’s it called. . . . psychokinesists, aren’t you.”

[Dr. Bose just shook his head. At this point, a voice shouts out, “Hey, Isaac have you seen the statue of Atlas in Rockefeller Center?”]

Tourist: “No. Hey, wait for me.”

[And the tourist runs off].

[curtain falls]

Moral of the play: Don’t play Monte with physicists.

Postscript: Rumor has it that Mayor Guiliana is proposing a new ordinance to prohibit the playing of Bose-Einstein Monte in public places in New York City.

The above play perfectly illustrates a Bose-Einstein condensate. When a Bose-Einstein condensate of a million atoms is achieved, the identity of each one is lost. If labels were placed on each atom to try to keep track of them, a person would have just as much trouble picking a particular atom out of the sample as the tourist had in selecting a numbered ball under a cup. It would be as if all the atoms had cups over them, hiding their identity. Each time an atom in a particular position in the condensate is picked, a random atom of the sample is selected. The atoms have lost their individuality. Of course, one cannot implement a Bose-Einstein version of Monte: the temperature is too high and the objects are too big. A Bose-Einstein condensate needs to have a very low temperature to allow the bosons to “stick together” and the bosons must be microscopic so that quantum mechanical effects are important.