a/n: My team wrote this review on quantum simulation as part of a seminar on quantum physics during summer 2021. While I’ve been a physics enthusiast since 8 years old, then I’d only taken a quantum computing class and didn’t have a strong background. I tried my best to learning 5+ hours a day reading resources online and, also attending additional lectures/workshops at 1 am my time zone. Aside from this review, our deliverables also included a final presentation on finite potential wells and weekly technical presentations.

Abstract

With the development of quantum physics, quantum simulation technology has become more mature and has many applications in real life. This paper introduces two methods of quantum simulation: ultracold atom simulation and integrated photonic simulation. First, ultracold simulation is easy to observe and highly manageable, and its experimental results often agree with the theory. Besides these, it also has limitations. Thus, how to surpass the general theoretical simulation is essential in the future. Then for integrated quantum photonics, it is easy to manufacture, available at room temperature and allows long simulations with a high degree of experimental control. With a few components optimized, large-scale quantum photonic circuits with many photons can likely become a reality in the coming decade.

Introduction

Since the early 20th century, quantum mechanics has become one of the most basic theories in the cognition of nature, a discipline to explore the physical laws of the micro world. The microscopic behavior of all physical systems or phenomena should meet the basic principles of quantum mechanics, so the simulation principle of any physical system should be based on quantum mechanics rather than classical physics. As the main content of quantum computing and quantum information science research, quantum simulation is to simulate and study the system that is unfamiliar or difficult to control by using a controllable quantum system.

Quantum simulation is a concept created by Feynman in 1982. To solve the problem that classic computers cannot simulate the quantum system accurately, Feynman suggested using a manageable quantum device to simulate the quantum behavior in other systems, which was the original motivation for the development of quantum computing, as quantum simulation has high requirements for computers with a large number of calculations [1]. For example, in quantum chemistry, classic computers cannot even simulate the behavior of molecules in median size. In condensed matter physics, quantum simulation is an ideal platform for research in a quantum phase transition and high-temperature superconductor (HTS) [2]. Methods for quantum simulation have sprung up in decades, and therefore a paper to summarize and compare the methods is necessary for the efficiency of future study. This paper summarizes two methods for quantum simulation, ultracold atom simulation and integrated photonic simulation. Firstly, for ultracold atom simulation, its reasons for being an ideal platform for quantum simulation, such as the considerable controllability of ultracold atoms, will be introduced, along with a discussion of the technical advantages of ultracold atom simulators challenging ideas. Then for integrated photonic simulation, it aims to combine photon sources, routing, optical processing and photon detectors on one chip for practicality, and its necessity in the quantum simulation will be demonstrated in this paper.

2. Ultracold atom simulators

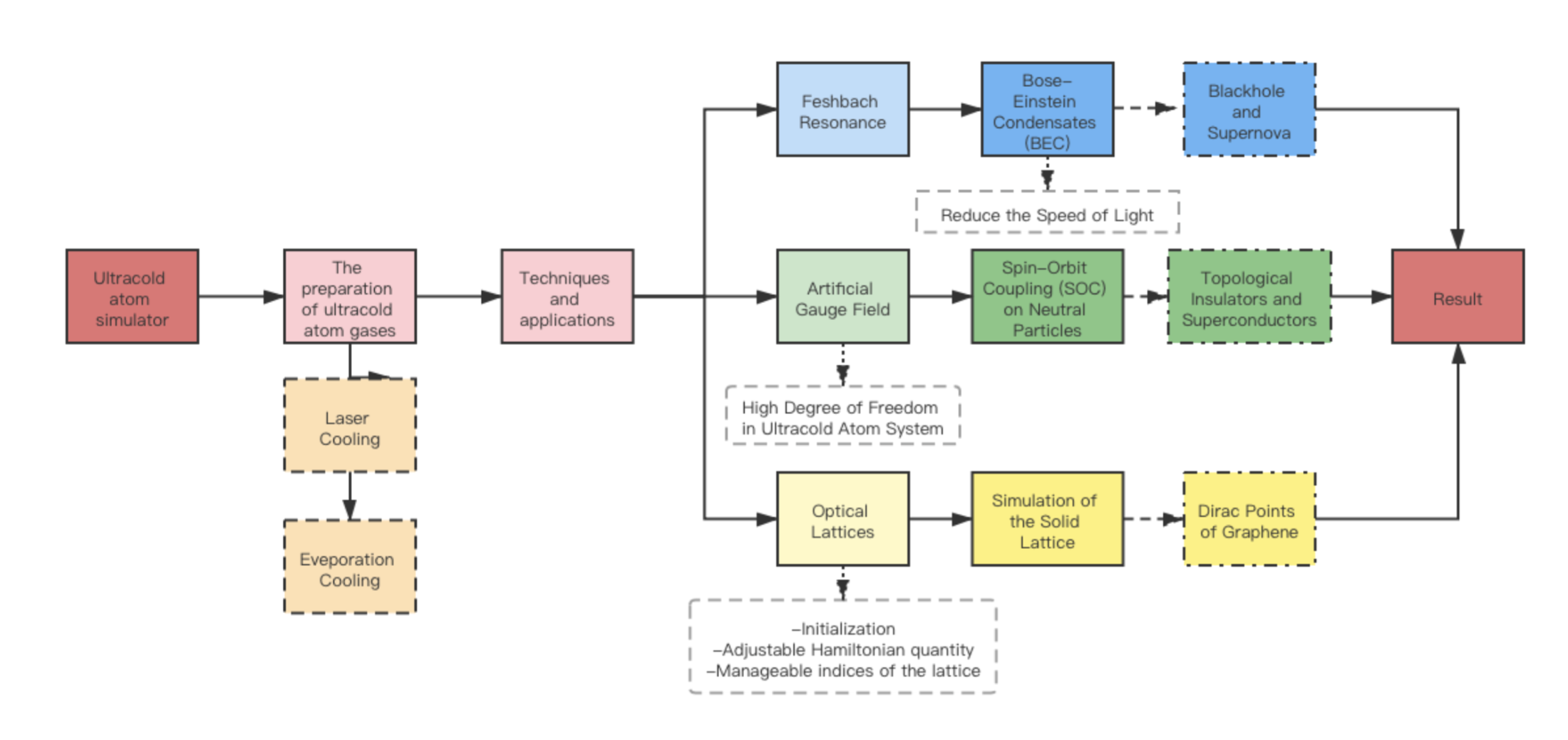

Figure 1. The mind map of this section.

Figure 1. The mind map of this section.

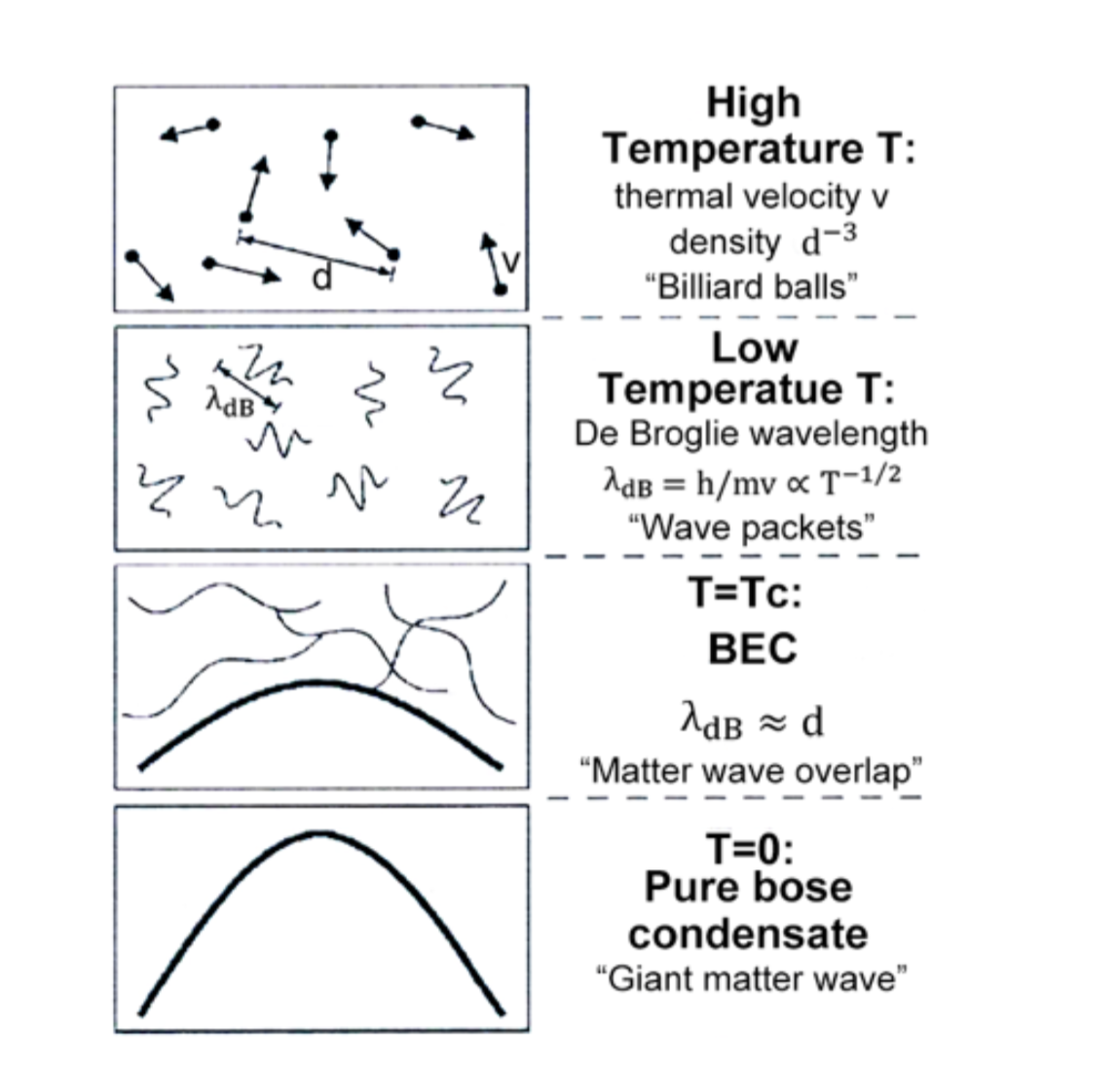

The speed of atoms at room temperature is about 300 m/s [3]. However, there is a downward trend in the momentum of atoms with a decrease in temperature, and therefore an increase in de Broglie wavelengths of particles, according to the momentum equation and de Broglie relation in quantum physics $p=\frac{3}{2} kt$ and $λ=h/p$ when de Broglie wavelengths of atoms are the same as the distance between atoms, Bose-Einstein Condensates (BEC) forms, as shown in Figure 2 [4].

Figure 2. The formation mechanism of BEC [5]. Particles move like billiard balls at high temperatures. De Broglie wavelength and volatility of particles increase while temperature decreases, and therefore it moves like wave packets. At the critical temperature, or degeneracy temperature, de Broglie wavelength of atoms is the same as the distance between atoms, atoms interfere with each other, and BEC forms, with quantum effects like tunneling effects clearly shown in the behavior of atoms [6].

Figure 2. The formation mechanism of BEC [5]. Particles move like billiard balls at high temperatures. De Broglie wavelength and volatility of particles increase while temperature decreases, and therefore it moves like wave packets. At the critical temperature, or degeneracy temperature, de Broglie wavelength of atoms is the same as the distance between atoms, atoms interfere with each other, and BEC forms, with quantum effects like tunneling effects clearly shown in the behavior of atoms [6].

Ultracold atoms are defined as atoms at extremely low temperatures, usually in the magnitude of $10^{-3}$ - $10^{-9}K$. Ultracold atom gases are neutral and thin, whose density is usually in the magnitude of $10^{13}-10^{15}cm^{-3}$ [4]. At a low temperature, the elastic and inelastic scattering of particles is controlled by quantum mechanical effects such as resonances or tunneling through barriers since the de Broglie wavelength becomes comparable to the range of the interparticle interactions. Prominent quantum effects, combined with high purity and high handling of electromagnetic fields, make ultracold atoms an ideal platform for quantum simulation.

The ultracold atom system is highly manageable. In solid materials, the internal structure is fixed by the rigid structure of materials. In contrast, in ultracold atom experiments, factors like the dimensions of the potential well, indices of the light field, number of atom gases, temperature, and the strength of the magnetic field can all be regulated according to the requirements of the experiment [7]. This is how quantum simulation is done in subsections.

2.1 Preparation of ultracold atom gases.

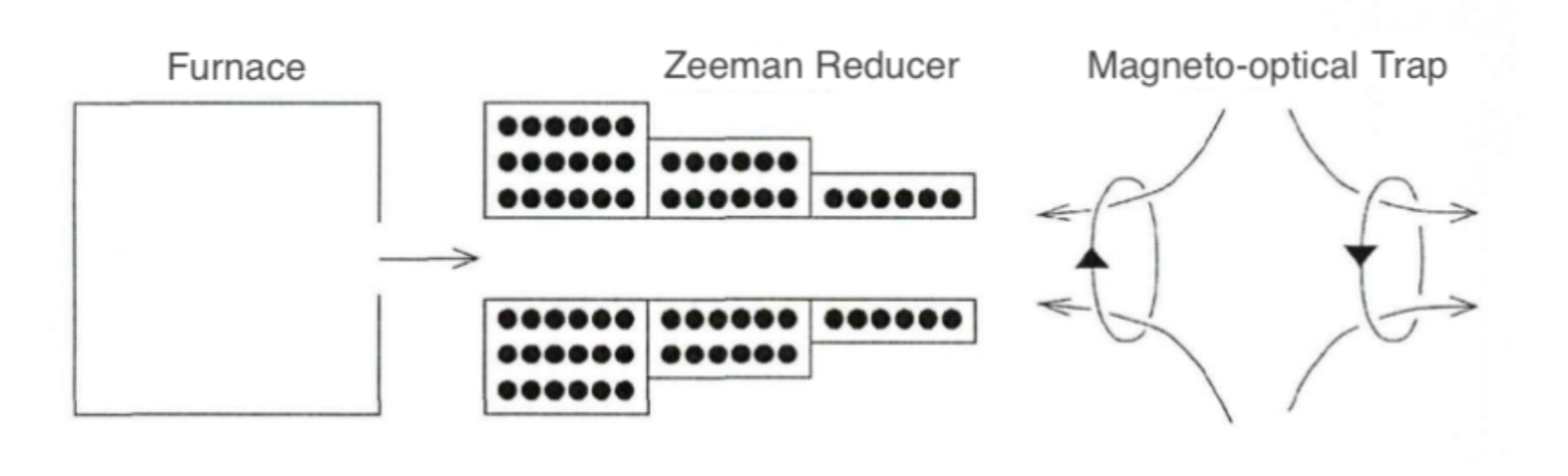

Preparation of ultracold atom gases needs the combination of many sets of technology. In the procedure, atoms are made cooled and trapped by the laser and evaporation cooling technique and the magnetic trap. The key of the first step is the Doppler cooling and Zeeman effect. The Zeeman reducer coordinates with a magneto-optical trap in this step. As atoms gain and lose kinetic energy respectively when transmitting and absorbing photons, it receives recoil force from photons. According to the Doppler effect, the frequency of incident light sensed by atoms with different speeds is different, and therefore they receive force with different magnitudes. Thus, regulating the incident frequency in different directions and altering atoms’ resonant frequency according to the Zeeman effect, a force opposite to the direction of atomic motion exerts on atoms to decrease the speed of atoms.

Consequently, atoms can be trapped by the magneto-optical trap, and a further step of Doppler cooling makes the temperature of atoms down to approximately 100 μK. However, there is a lower temperature limit for the laser cooling technique, as the spontaneous radiation can warm up the atoms. In the second step, the evaporation cooling technique enables the atoms with relatively high energy to escape the system, lower the average energy level of atoms left, and therefore degeneracy temperature is reached, and BEC forms [8].

Figure 3. A typical experiment to cool and trap atoms.

Figure 3. A typical experiment to cool and trap atoms.

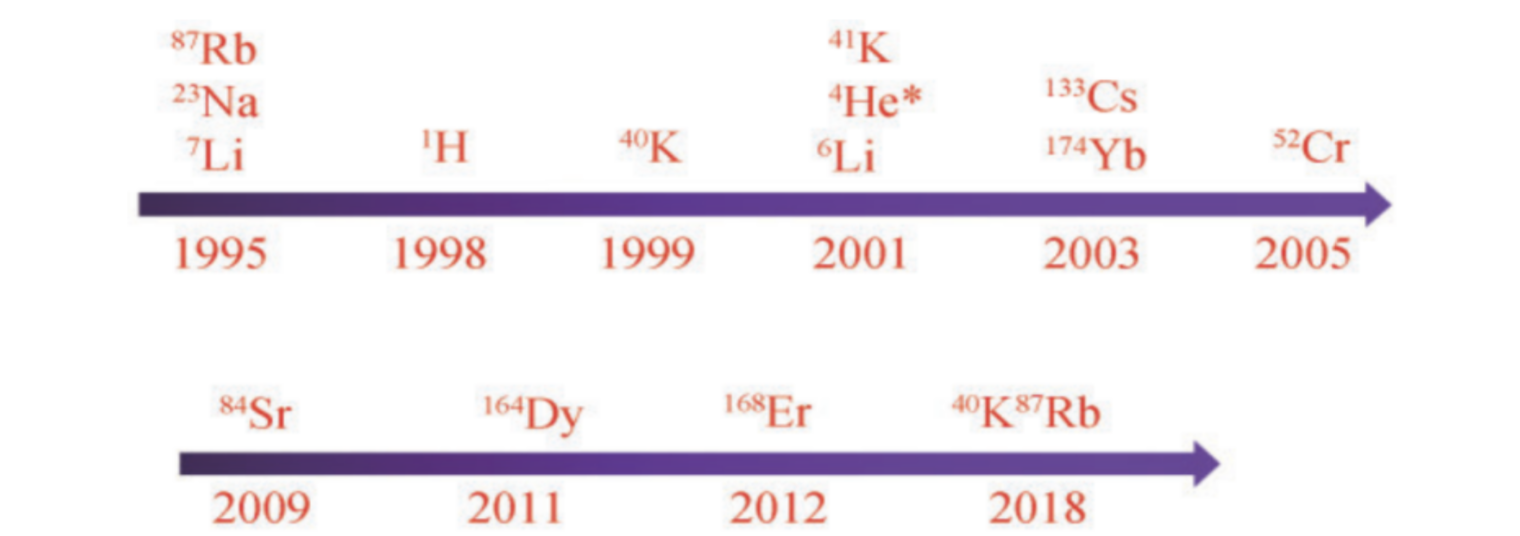

The timeline in figure 4 shows the time point when some important ultracold quantum degenerate gases are realized, meaning that after decades of development, the technique to prepare ultracold atom gases is quite mature.

Figure 4. The timeline of the realization of important ultracold atom degenerate gases [9].

Figure 4. The timeline of the realization of important ultracold atom degenerate gases [9].

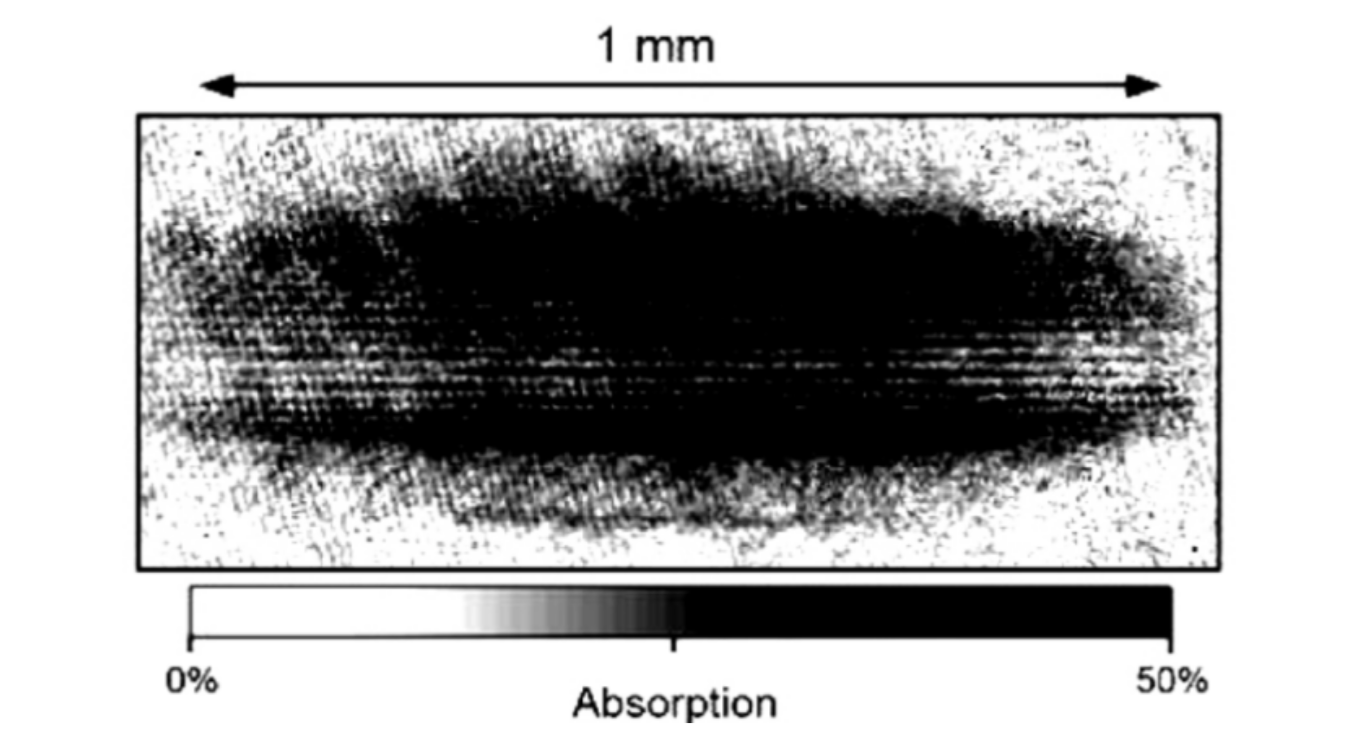

2.2 Bose-Einstein condensates and Feshbach resonance

The BEC is a gaseous, superfluid matter of a boson atom whose temperature is close to absolute zero. Almost all atoms are concentrated in the quantum state with the lowest energy, forming a macroscopic quantum state [10]. BEC has volatility and coherence like lasers, so interference between two laser beams can also occur between two condensates, observed by W. Ketterle [11]. Figure 5 shows the interference between two condensates, with a slit clearly shown. The properties of the wave and the unique state of matter explain why BEC is a good media for quantum simulation [5].

Figure 5. The interference observed by Professor Kettlerle between to BECs.

Figure 5. The interference observed by Professor Kettlerle between to BECs.

BEC has a high optical density difference. Lasers can change the state of atoms in the condensates so that there is a sudden increase in the refractive index of condensates, and the speed of light drops immediately, even to several meters per second. That is why BEC can be made a model for a black hole, as light is “frozen” in the condensate [12].

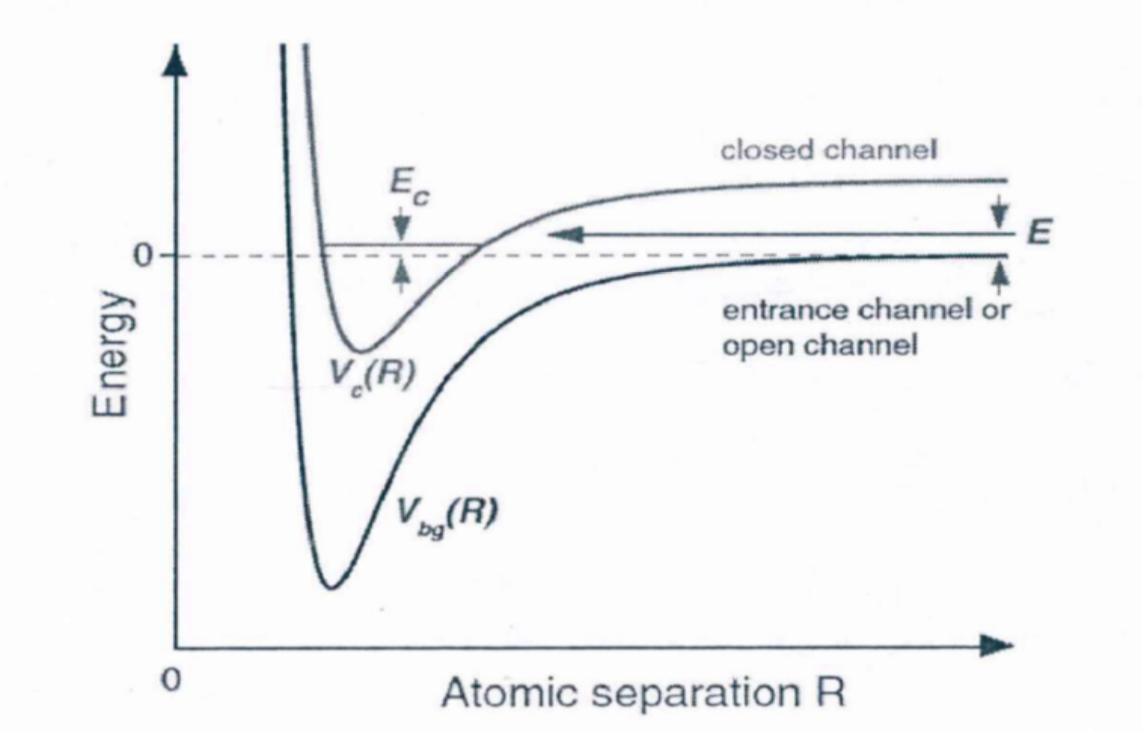

Thus, the unique properties of BEC make it ideal for lots of research in quantum physics and applications. In a closed channel, the atomic motion is constrained, and the channel wave function gradually disappears at infinity, while in an open channel, the atomic motion is not constrained, and the channel wave function oscillates at infinity asymptotically. The typical s-wave scattering length of alkali metal atoms is between 50 and 100 Bohr radii, and the distance between atoms is about 1.4 Bohr radii. In comparison, the interaction between atoms is very weak. Through Feshbach resonance, people can use the magnetic field to adjust the scattering length of the ultra-cold atoms in the open channel, and therefore adjust the strength of the interaction between the atoms. Feshbach resonance is an important technique for the simulation [7].

Figure 6. The diagram of the Feshbach resonance. By adjusting the energy difference between the open channel and the closed channel, the atoms in the open channel can undergo a resonance process with a divergent scattering length [4].

Figure 6. The diagram of the Feshbach resonance. By adjusting the energy difference between the open channel and the closed channel, the atoms in the open channel can undergo a resonance process with a divergent scattering length [4].

The application of Feshbach resonance benefits from the advent and development of the optical trap. Ultracold atoms are trapped in the optical trap, and therefore they escape from the attraction of the magnetic field. Feshbach resonance provides a method to adjust the external magnetic field so that the strength of particle interaction can be regulated artificially [13]. The transformation from BEC to Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) superfluid is realized by regulating the interaction intensity between fermions. This technique can simulate the outburst of the supernova and black hole in BEC, control the generation of solitons, etc.

2.3 Spin-orbit coupling and artificial gauge field

In condensed matter physics, spin-orbit coupling comes from the movement of electrons in the inherent electric field of the atom itself, which is the core content of the Spin Hall effect, topological insulation, topological superconductors, Majorana fermions, spintronics, etc. Besides, it can also be extended to quantum computing [3].

It is mentioned above that ultracold atoms are electrically neutral. However, SOC merely exists on charged particles in the natural world. That is why the research of SOC only applied to the fermion system in the past, while the research on the boson system, which is the majority in the real world, was nearly empty. However, this limitation is removed in the artificial gauge field, with the interactions between atoms and light being regulated. In other words, spin-orbit coupling (SOC) on neutral particles is realized. It was first realized in 2009 by Spielman [14].

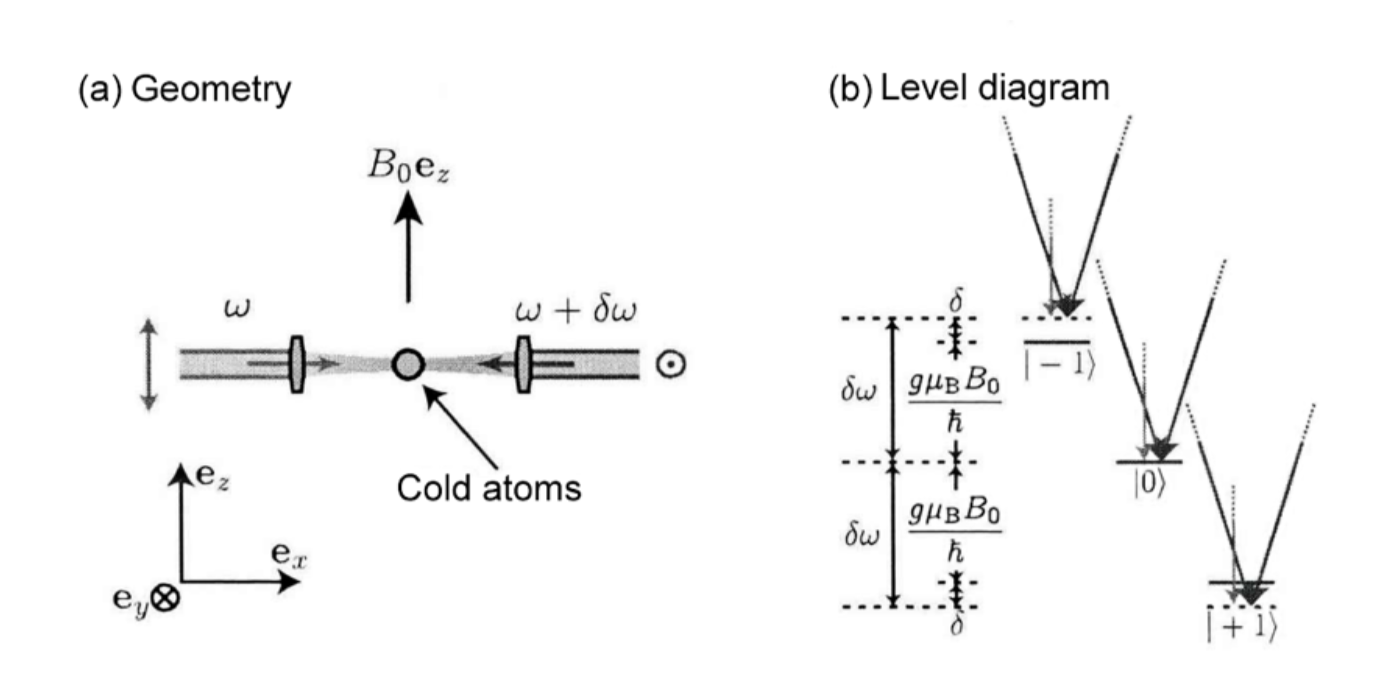

Figure 7. (a) General experiments with two light beams, (b) The energy level structure of three-energy-level atoms in the experiments.

Figure 7. (a) General experiments with two light beams, (b) The energy level structure of three-energy-level atoms in the experiments.

Figure 7 shows the basic idea of Spielman’s method. The particles considered in the methods are alkali metals Rb-87 and K-40, whose electron structure in the ground state is $2S_{1/2}$. Two back-propagation Raman laser beams trigger this kind of SOC along the x-axis, combined with a magnetic field on the z-axis. For one of the two laser beams, $\pi$, its polarization direction is along the z-axis, while for the other one, $\sigma$, it is along the y-axis. With the two laser beams, a biphotonic process is experienced by atoms. First, the photons are absorbed, and the particles are excited to the intermediate state $2P_{1/2}$ and $2P_{3/2}$. Then a photon in another type is transmitted so that atoms return to the ground state [15]. With indices flexibly changed in the ultracold atom system, the condition hard to reach in the real solid materials can be simulated, and new phenomena can be discovered. A typical example of this is topological insulators and topological superconductors.

2.4 Optical lattices

In the solid lattice, the distance between atoms is small, and therefore the interactions between atoms are great. On the contrary, the distances between lattice points and atoms are large in the optical lattice, so the interactions are small. As a result, particles’ dynamical property and time evolution in the optical lattice are very slow compared to the solid lattice. However, the mode of motion and equations of motion of atoms in the optical lattice are similar to that of electrons in the solid lattice. Thus, using BEC in the optical lattice to simulate the solid lattice system is feasible. Phenomena that are hard to be observed in the solid, such as the Bloch oscillation, nonlinear Landau-Zener tunneling, etc., can be observed in the optical lattice. In addition, simulation of the complicated model in the condensed matter and the optical system can be realized as the optical lattice technique. The detailed calculations can be found in the review.

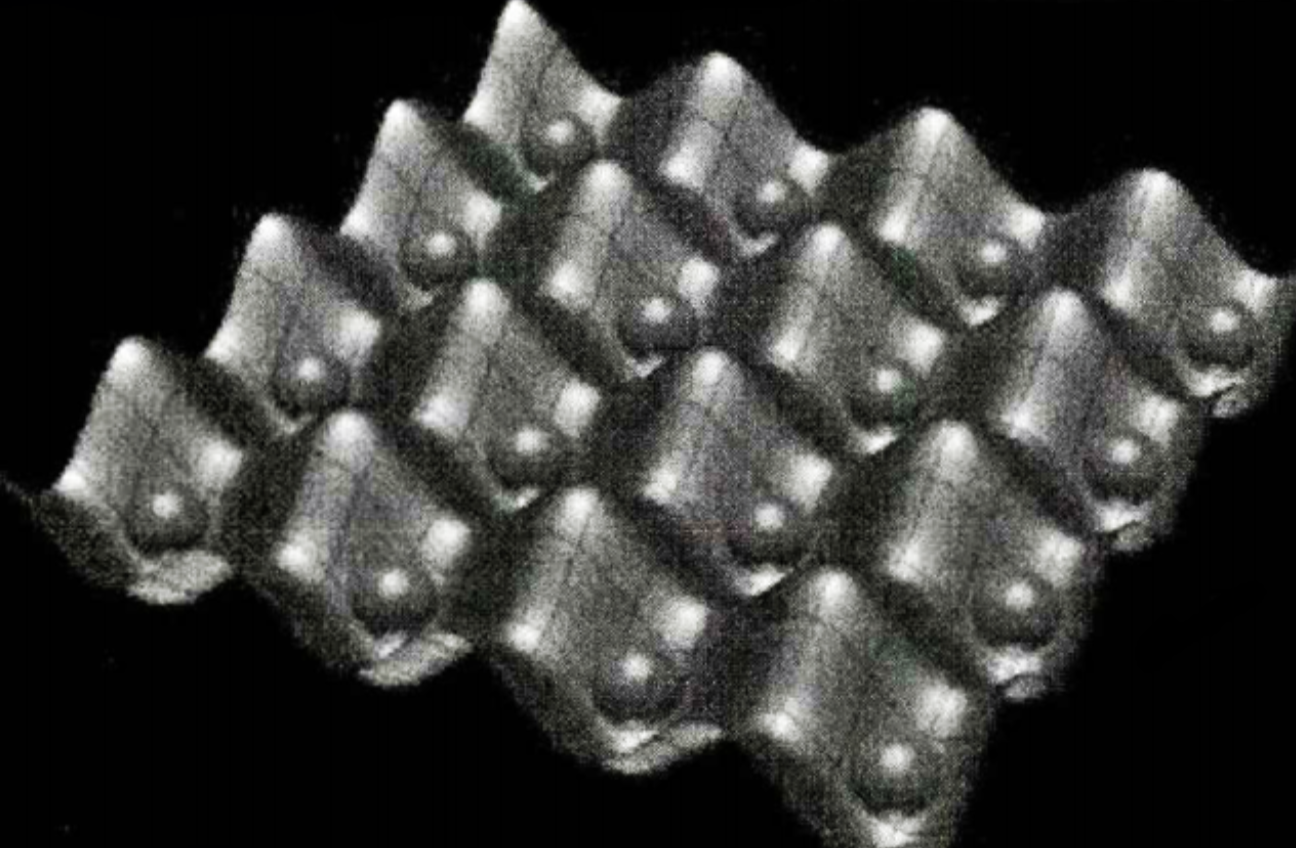

Figure 8. The general model of optical lattices [14].

Figure 8. The general model of optical lattices [14].

The optical lattice is mainly realized by the AC stark effect between light and atoms. A periodic potential well is obtained using overlapping laser interferences in the optical lattice. The system can realize the initialization of many particles by using the existing experimental technology; the Hamiltonian quantity is also easy to adjust; by regulating the potential field of the optical lattice, the lattice structure and dimensions can also be changed. By adjusting the direction, quantity, angle, polarization, and frequency difference of the incident laser beams, a variety of 1-dimensional, 2-dimensional, and 3-dimensional optical lattices can be realized, and different potential fields can be added to the original optical lattice, thereby realize the quantum simulation of various Hamiltonian [16].

In a typical condensed matter system, electron motion can be seen as the lattice produced by the nucleus, which can be simulated by the optical lattice technique in an ultracold atom system. Take graphene as an example, one of the most promising materials in many fields, with electrical conductivity and strength. With the help of the optical lattice technique, Dirac points, the important structure in the graphene, can be simulated in the ultracold atom gas. Dirac points are the core of numerous new physics phenomena like the massless electrons in the graphene and the conductive boundary state of the topological insulation.

2.5 Results

The great achievements of the quantum simulation obtained in the decade have benefited from the favorable quantum nature of the ultracold atoms. Additionally, the optical lattice technique is also a key factor. The Feshbach resonance made the research on the intersection of BEC and BCS possible, and therefore the simulation of the complicated physical system like black holes, boosting the astronomy research. The artificial gauge field broke the limit that the ultracold atoms are neutral and realized the SOC on the boson system, filling the gap in this field. The research of aggregating dimensions can be seen as an expansion of the optical lattice, bringing new ideas for future research in quantum simulation.

Due to the purity of ultracold atoms, experimental results often agree well with the theory. Therefore, quantum simulations of ultra-cold atoms are often criticized as repeated verifications of theories. Nonetheless, while achieving great results in ultracold atom quantum simulation, we also see its limitations and bottlenecks. Thus, how to surpass the general theoretical simulation is a key point in the study of ultra-cold atom quantum simulation. The interaction between atoms makes our research work beyond the general single-particle image and enter the field of multi-body physics. This is a feature and advantage of ultra-cold atom quantum simulation and an important aspect of its scientific significance. Finding a new foothold is the key to development. In recent years, topological quantum simulation research has developed rapidly in ultracold atomic systems, which is an important direction. But at the same time, we must also see that topological quantum simulation is also developing rapidly in systems such as phonons and photons. In addition, in recent years, the direction of quantum computing has been greatly developed, especially the superconducting qubit system, which has greatly improved its quantum simulation capabilities. In addition, in recent years, the direction of quantum computing has been greatly developed, especially the superconducting qubit system, which has greatly improved its quantum simulation capabilities [9].

3. Integrated Quantum Photonics

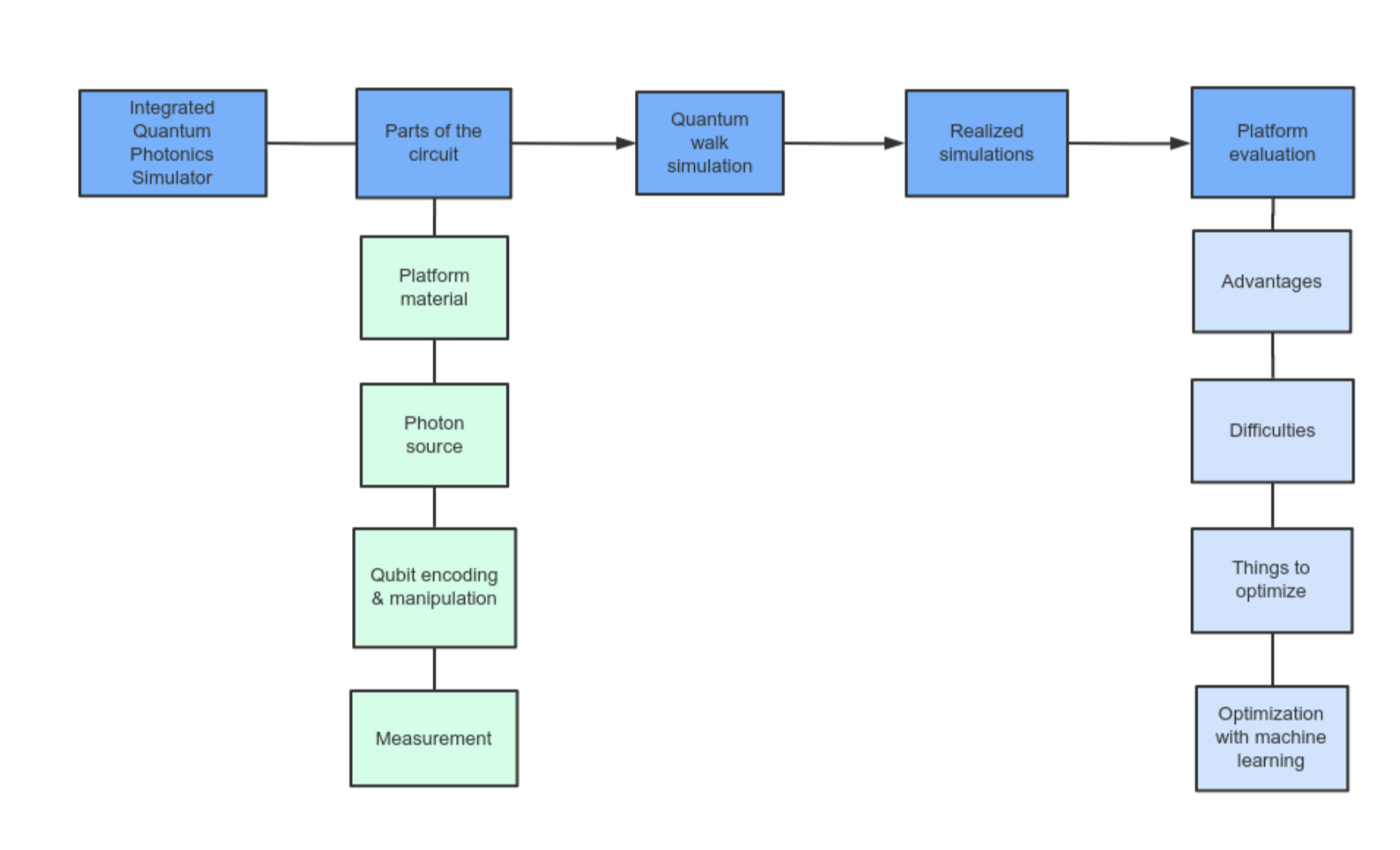

Figure 9. The flowchart of this section

Figure 9. The flowchart of this section

Integrated quantum photonics aims to combine photon sources, routing, optical processing and photon detectors on one chip for practicality.

3.1 Parts of the circuit

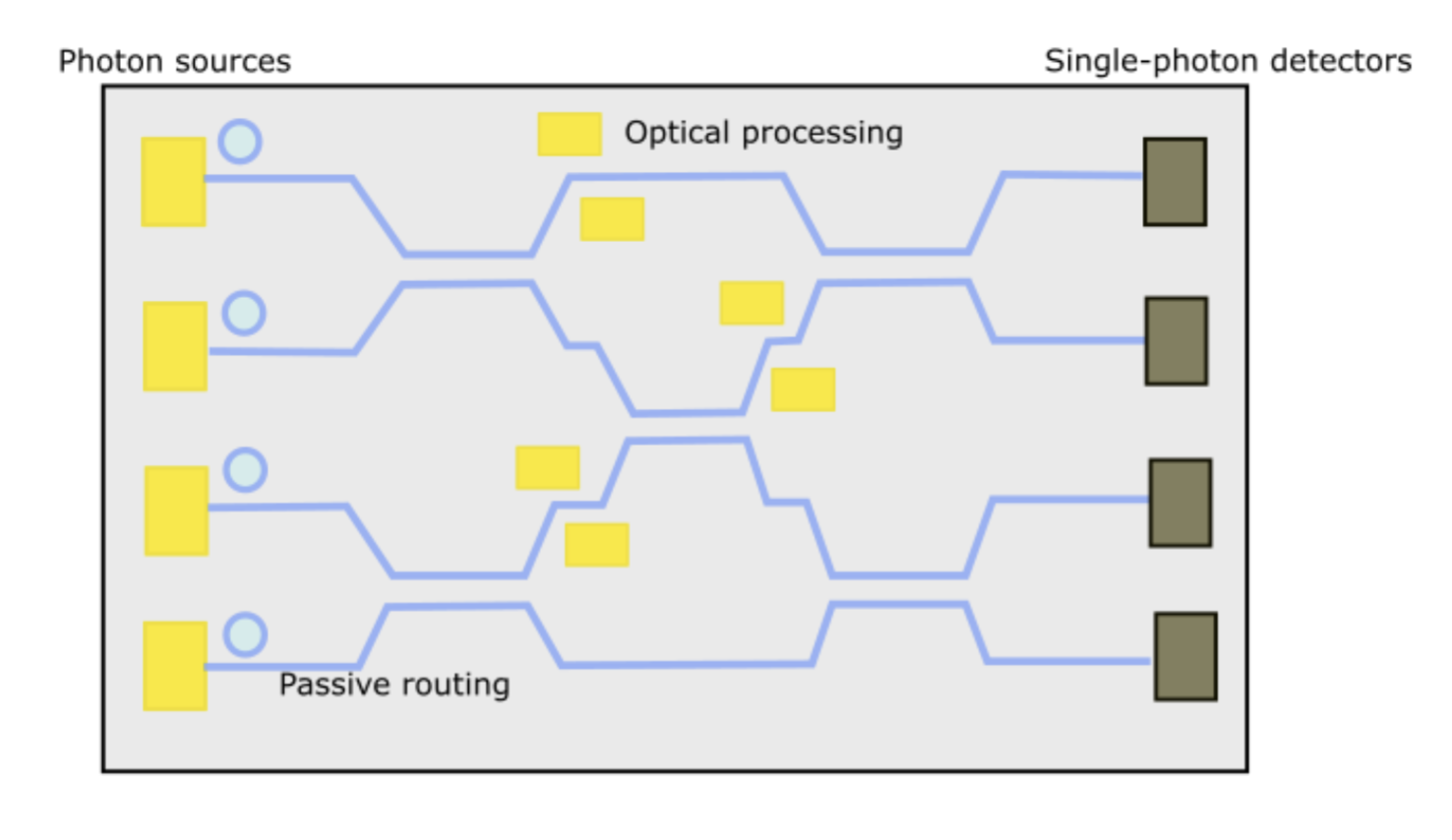

Figure 10. The scheme of an integrated quantum photonic circuit.

Figure 10. The scheme of an integrated quantum photonic circuit.

3.1.1 Platform material.

Due to the variety of optical components involved, various materials can be used as the substrate. For example, LN, GaAs, and InP are materials whose electro-optical effects allow fast manipulation of single-photon states. At the same time, silicon waveguides(the photonic equivalent of a wire) can keep light well confined with silicon’s high refractive index, layered on silica [17, 23]. A higher index contrast allows smaller optical components.

3.1.2 Photon source.

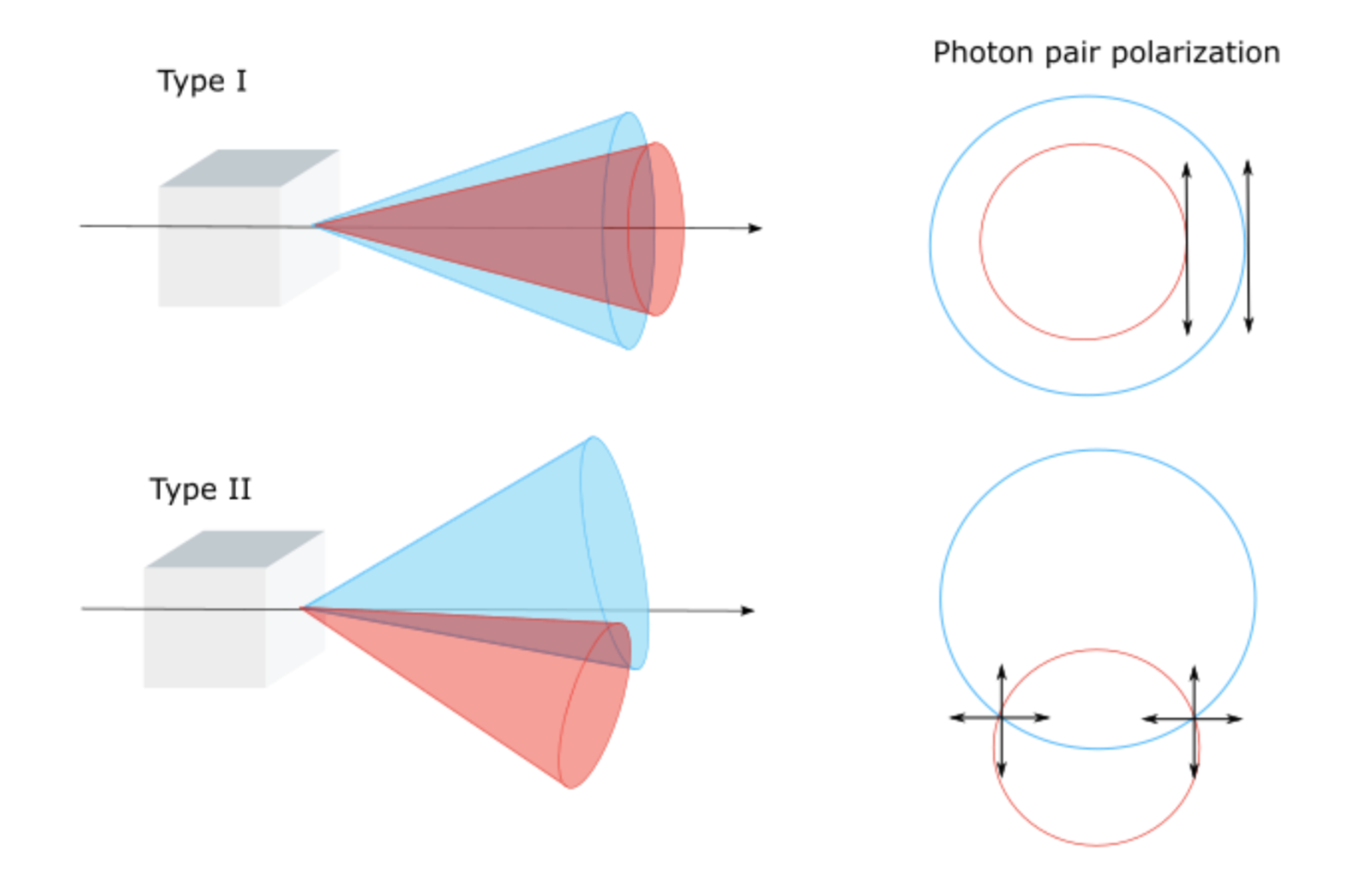

Integrated quantum photonics relies on single-photon sources on the circuit. A single photon can be generated when a laser pulse strikes a particular type of semiconductor aka a quantum dot. Presently, the best performance is achieved by self-assembled InGaAs/GaAs materials [17]. Likewise, a pair of entangled photons can be generated via a crystal, such that depending on the input photon’s polarization, two output photons will either share identical or orthogonal polarizations [18]. (see figure 2) Many other processes including the spontaneous four-wave mixing process can be used to polarize photons, with two photons being inputted.

Figure 11. Parallel(Type 1) and orthogonal(Type 2) polarizations of entangled photons generated in the process of Spontaneous Parametric Down Conversion.

Figure 11. Parallel(Type 1) and orthogonal(Type 2) polarizations of entangled photons generated in the process of Spontaneous Parametric Down Conversion.

3.1.3 Qubit encoding and manipulation

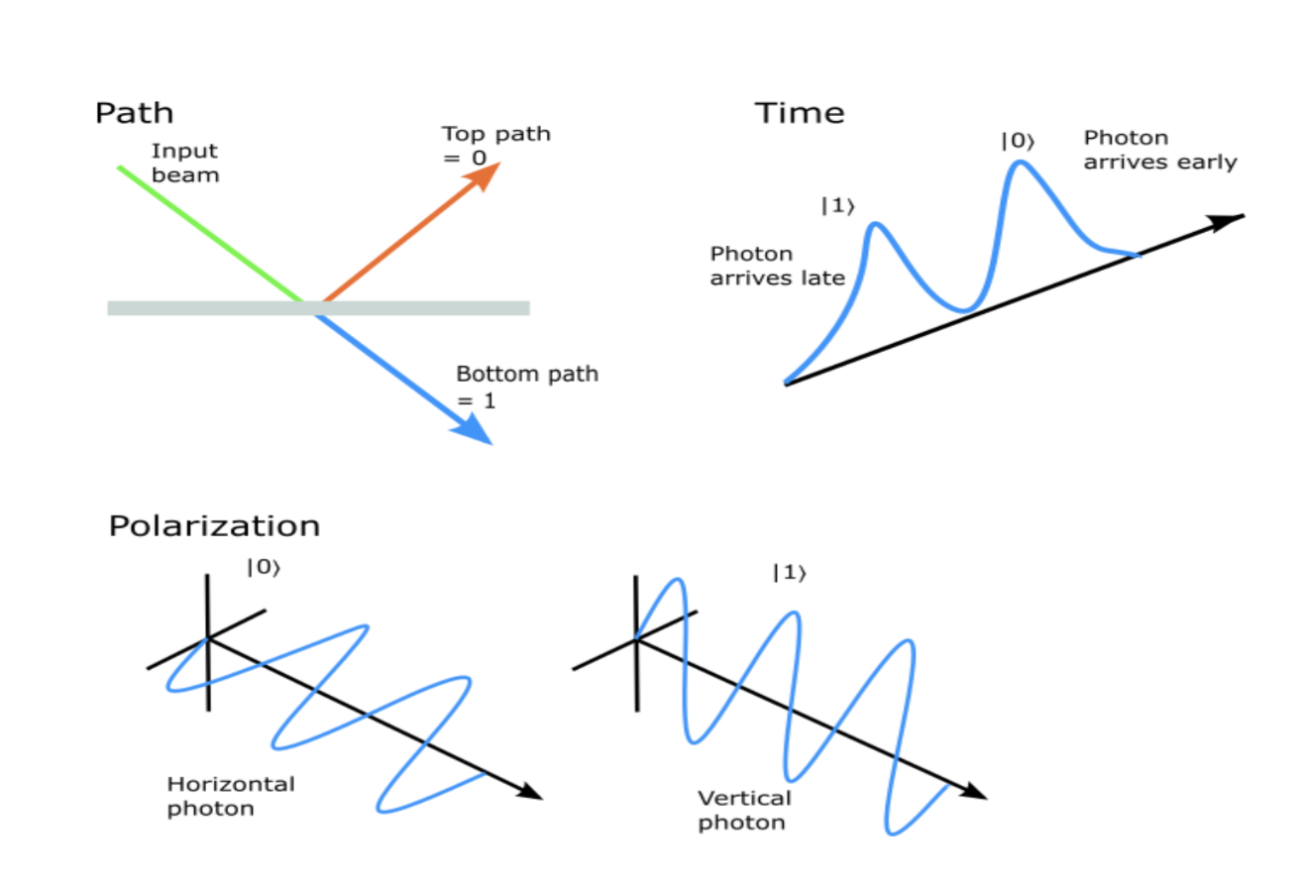

Input variables in an algorithm are often encoded in the path, polarization, time of the single-photon, though many other methods exist [19].

Figure 12. The three main types of photons encoding.

Figure 12. The three main types of photons encoding.

Photons are routed through the circuit by silicon waveguides, and when two waveguides come close together, they can form directional couplers that effectively divide light. Some examples of directional couplers are power splitters, polarization splitters and wavelength (de)multiplexers. Aside from the above passive elements, there are active elements that reconfigure the circuit. For example, phase shifters controlling phases of interferometers; polarization transformers and space switches acting as tunable beam-splitters. These active elements cannot be expected to operate identically in each use. Thus, they are a source of stochastic noise [20]. If multiple substrates are used, it is necessary to have interfacing components such as fiber waveguide coupling and dielectric mirrors.

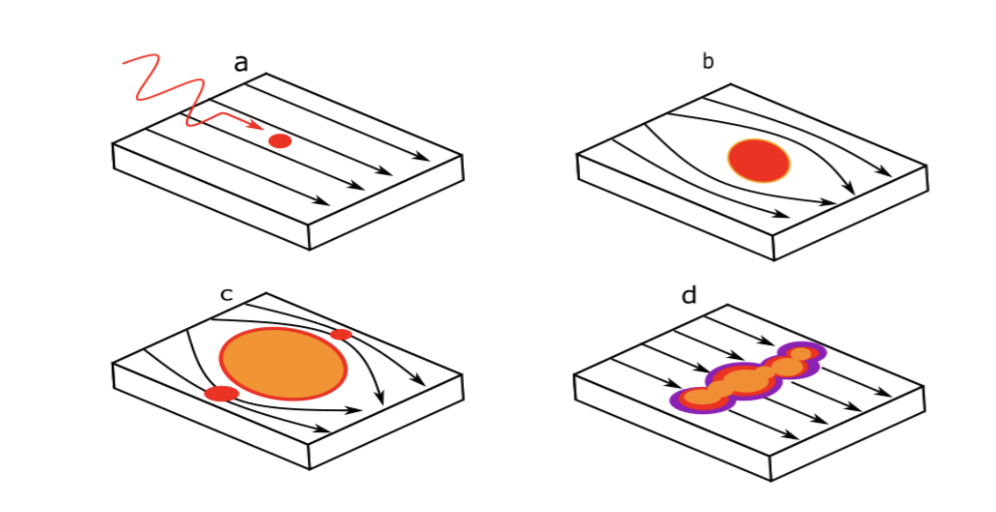

3.1.4 Measurement

Quantum information is eventually read out by on-chip single-photon detectors (SPDs). One such technology uses a superconducting nanowire for detection. A superconductor carries electricity without friction, yet there is still a limit on the current passing at once. In SNSPD, a segment of the wire is charged with maximum current, such that when a photon passes by, it causes a decrease in the current limit, leading to a short loss of superconductivity. This change creates an electrical signal to record the passing photon [21].

Figure 13. a. A photon enters the nanowire, creating a hot spot

b. Superconductivity is disrupted

c. A resistive region starts to span the entire region of the nanowire

d. A measurable voltage is induced across the device

Figure 13. a. A photon enters the nanowire, creating a hot spot

b. Superconductivity is disrupted

c. A resistive region starts to span the entire region of the nanowire

d. A measurable voltage is induced across the device

SNSPDs can achieve high detection efficiency. However, the chip needs to be placed in a cryostat containing, e.g., liquid helium [22].

Another detector, transition-edge sensors, has higher efficiencies, limited speeds and must be cooled to millikelvin temperatures for operation. Similarly, silicon avalanche photodetectors have a moderate efficiency but are significantly low speed [23]. Still, many quanta photonic functions are integrated with electronics to provide DC power, control and I/O with the classical world [2].

3.2 Quantum Walk Simulation

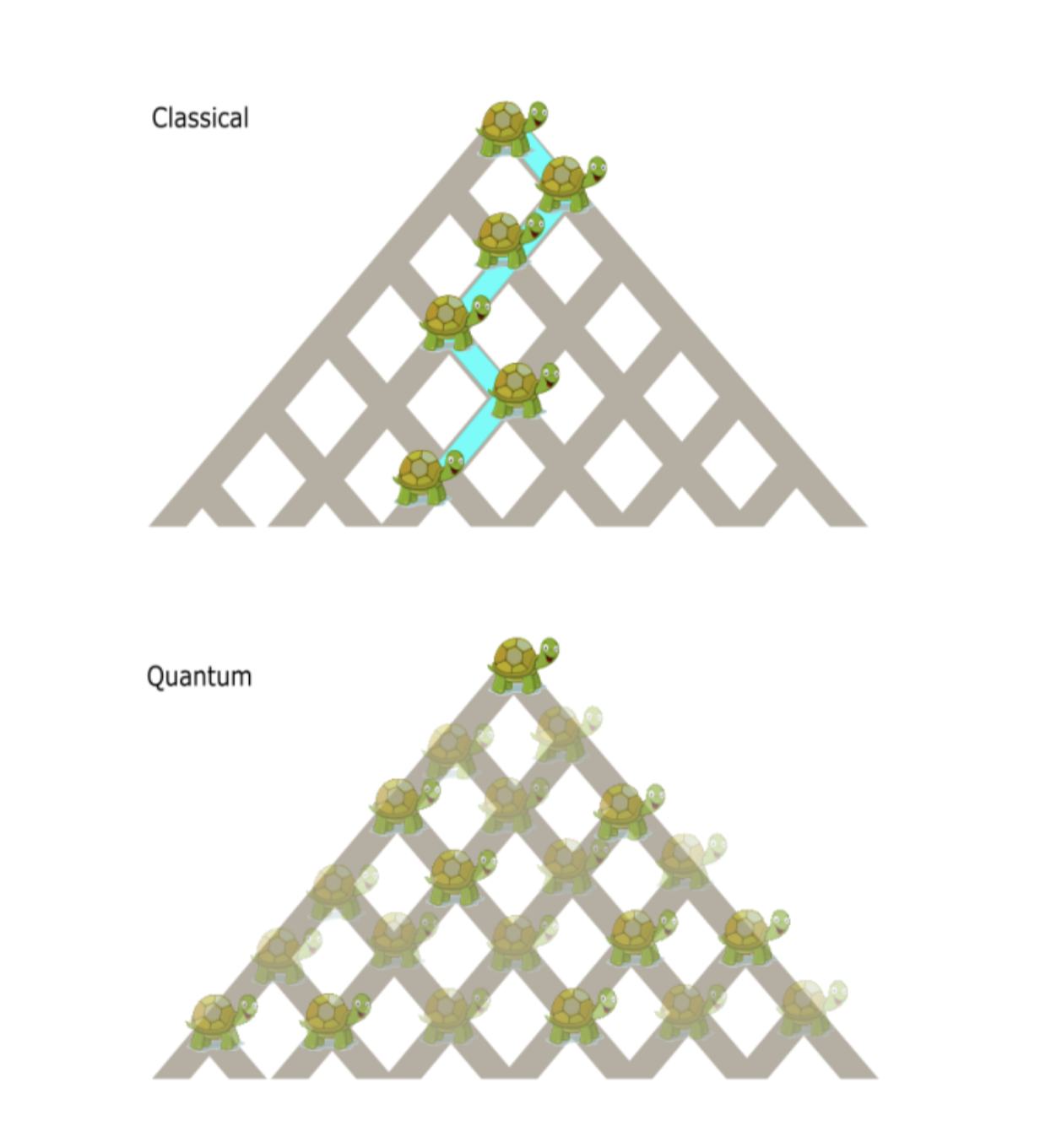

Photonics is an exceptional platform for performing large-scale quantum walks. A walk is a distribution occurring over a given graph following a defined equation of motion [24]. A quantum walk model describes the coherent propagation of quantum particles in networks [25]. (see figure 14.)

Figure 14. Comparing classical walks with quantum walks

Figure 14. Comparing classical walks with quantum walks

The quantum walk is a powerful tool: It could explain energy transport in photosynthesis; emulate Darwinian evolution, quantum biophysics, systems with properties beyond standard models; solve isomorphism problems, realize universal quantum computation and build quantum algorithms [26, 28]. The well-known Grover’s search algorithm can be viewed as a quantum walk algorithm [27]. Similarly, the computation for the boson sampling problem, which is essentially asking, “What is the distribution of photons?” can be massively simplified by running on a quantum photonic device and is key in demonstrating quantum advantage with current technology [29].

Due to the long coherence times of photons, long evolutions of quantum walks can be simulated while giving a high degree of experimental control. One technique using femtosecond lasers can draw precise three-dimensional waveguide networks within the glass. As the third dimension is used to propagate the wave, this allows the simulation of two-dimensional quantum walks [28].

In the past decade, demonstrations ranged from single particles walking on two-dimensional lattices to multiple particles interfering on one-dimensional structures to multiple photons evolving on a two-dimensional platform [26]. They have been simulated using bulk optics and waveguides.

3.3 Realized simulations examples

Molecules can be simulated using near-term devices. In 2018, the eigenvalues of the ground and excited states of molecules, e.g., hydrogen was approximated on a programmable silicon photonic chip, using a combination of quantum phase estimation and variational eigensolver [22]. The results were estimated with 32 bits of precision with fidelities > 99%. The vibrational dynamics of four-atom molecules, e.g., ammonia, sulfur trioxide, energy transport in a protein fragment and a water molecule reaching thermal equilibrium were simulated [37]. Simulations can be evaluated using Hamiltonian learning, where a small, trusted quantum simulator verifies a large untrusted one [31]. In 2020, a quantum advantage was demonstrated on the bulk photonics quantum computer Jiuzhang by implementing a type of Boson sampling with 76 photons [29].

3.4 Platform evaluation.

Integrated quantum photonics is a promising candidate in simulating complex systems. The speed of photons allows interaction between a large number of components that are already supported by the mature CMOS fabrication process, providing the basis for scaling up [20]. The current classical PICs contain thousands of components in a few microns, but millions of components may be contained in the future [20]. The platform can run at room temperature and does not need to be isolated, reducing costs. Since photons do not interact with the environment easily, they have close to maximum-possible coherence time meaning many operations can be performed [20].

However, this non-interactive property also implies difficulty in making two-qubit gates, which are key in realizing universal quantum computing in the gate-based approach. Extreme devices such as the ultra-high-Q resonators are used, generating massive overhead, and the gate-based approach is considered impractical for scaling up [32].

In the one-way quantum computing approach, the difficulty presents in generating multiphoton entangled states in a relatively easy-to-implement circuit [30]. This approach is widely considered more realistic.

Currently, eight photons can be generated and processed in the same silicon chip [33]. Constructing devices with many qubits requires efficient single-photon sources, generating multiphoton entangled states that travel in a network of low-loss optical switches or waveguides. These are foundational to a fault-tolerant quantum computer. Once a sufficient number of photons are available, slight qubit loss will be sufferable, as the information can be recovered by applying Topological Error Correction [30]. Presently, photon counters are the only components that operate at cryogenic temperatures. By developing room-temperature photon counters, completely integrated photonic chips are possible. The room-temperature advantage can then be fully exploited.

In the near term, machine learning could speed up the design and experimental process.

For instance, a model was recently shown to recognize and select pure photon emitters with 95% accuracy and is 100 times faster than the conventional method [34]. Similarly, learning models are shown to have designed experiments more efficiently than the best previous approaches while rediscovering experimental techniques that are only recently becoming standard in quantum optical experiments [35]. Chip imperfections arising from manufacturing could be mediated with a combination of machine learning and on-demand programming of the chip [17]. Finally, machine learning could be used for validating quantum simulation data [36].

With these challenges solved, large-scale quantum photonic circuits with many photons can probably be used for simulation in the next decade.

4. Conclusions

Quantum computing and quantum simulation develop very fast; numerous achievements and new applications have spawned. This paper makes an overview of the past achievements of quantum simulation.

The advantage of ultracold atom simulators is the flexibility and purity, simulating the especially complicated physical cases and producing results with a high theoretical agreement. However, the future challenge in this field is to improve the uniqueness of the simulator since other techniques in quantum computing and simulation like superconducting quantum computers with high qubit numbers. This paper suggests that the key points of this are to lower the cost of material preparation and simulation and enlarge the range of cases and models it can simulate.

Likewise, the features of integrated quantum photonic simulators are the feasibility of manufacturing, the speed and the long coherence times of the qubit. The device can operate at room temperature except for one component. Much effort is needed to integrate this component onto a room-temperature chip and optimize several other processes, which can be aided by machine learning.

Those technologies may be used in many aspects in the future, and there are still some obstacles that need to be overcome. Through this, we hope more people can understand and interest in quantum simulation, and there will be more remarkable advances and amazing applications in the future.

References

[1] Feynman R P. Simulating physics with computers. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 1982, 21(6): 467-488.

[2] Georgescu I M, Ashhab S, Nori F. Quantum simulation. Review Modern Physics, 2014, 86(1): 153-185.

[3] Shen X 2018 Quantum Simulation and Detection of Topological Invariant in Ultracold Atom System D. University of Nanjing

[4] Pan J 2017 Quantum Simulation with Ultracold Atoms D. University of Science and Technology of China

[5] Ketterle W. Nobel lecture: When atoms behave as waves: Bose-Einstein Condensation and the atom laser. Review Modern Physics, 2002, 74(4): 1131-1151

[6] Staanum P, Kraft S D, Lange J, Wester R and Weidemüller M 2006 Experimental Investigation of Ultracold Atom-Molecule Collisions J. Physical Review Letters 96(2). doi:10.1103/physrevlett.96.023

[7] Peng P and Gao C 2020 The history of ultracold atoms J. Science. 72(01): 41-46+4

[8] Deng T 2019 Quantum Control in Ultracold Atomic Gases D. University of Science and Technology of China

[9] Yan B 2021 Quantum simulation based on ultracold atoms in a lattice J. Physics 50(01):31-36

[10] Han Z 2019 The Study of Numerical Method Based on Bose-Einstein Condensate D. Shenyang Normal University

[11] Xu Z, Li Y, Zhang X and Wu Z 2017 The physical exploration of Bose-Einstein Condensate J. Physical Experiment of College 30(03): 63-68.

[12] Zhou Z 2019 Coherent Control of Ultracold Atomic Regular and Chaotic Transport D. Hunan Normal University

[13] Feshbach H 1958 Unified theory of nuclear reactions J. Annals of Physics 5(4): 357-390

[14] Dong D 2015 Schemes in Cold Atoms about Quantum Simulation and Quantum Computation D. University of Science and Technology of China

[15] Goldman N, Juzeliunas G, Ohberg P and Spielman I B 2014 J. Rep. Org. Phys. 77126401

[16] Liu W, Zhou X, Jiang K, Liu L, Xia L, Li X 2019 Ultracold atom simulators based on artificial gauge field and the optical lattice J. China Basic Science 21(05):41-57.

[17] Spontaneous parametric down-conversion. (2021, March 16). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spontaneous_parametric_down-conversion

[18] What is a qubit? (2021, April 20). Retrieved from https://uwaterloo.ca/institute-for-quantum-computing/quantum-101/quantum-information-science-and-technology/what-qubit

[19] Rudolph, T. (2017). Why I am optimistic about the silicon-photonic route to quantum computing. APL Photonics, 2(3), 030901. doi:10.1063/1.4976737

[20] Kingery, K. (2017, December 15). Single-photon detector can count to four. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2017-12-single-photon-detector.html

[21] Pernice, W., Schuck, C., Minaeva, O. et al. High-speed and high-efficiency travelling wave single-photon detectors embedded in nanophotonic circuits. Nat Commun 3, 1325 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2307

[22] Santagati, R., Wang, J., Gentile, A. A., Paesani, S., Wiebe, N., Mcclean, J. R., . . . Thompson, M. G. (2018). Witnessing eigenstates for quantum simulation of Hamiltonian spectra. Science Advances, 4(1). doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap9646

[23] Moody, G., Sorger, V., Juodawlkis, P., Loh, W., Sorace-Agaskar, C., Jones, A. E., . . . Vidarte, L. T. (2021). Roadmap on integrated quantum photonics. Journal of Physics: Photonics. doi:10.1088/2515-7647/ac1ef4

[24] Aspuru-Guzik, A., Walther, P. Photonic quantum simulators. Nature Phys 8, 285–291 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2253

[25] Department Physik - Quantum Walks (Universität Paderborn). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://physik.uni-paderborn.de/silberhorn/forschung/quantum-networking/quantum-walks

[26] Jiao, Z., Gao, J., Zhou, W., Wang, X., Ren, R., Xu, X., . . . Jin, X. (2021). Two-dimensional quantum walks of correlated photons. Optica, 8(9), 1129. doi:10.1364/optica.425879 [27] Quantum walk. (2021, June 10). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_walk

[28] Gräfe, M., Heilmann, R., Lebugle, M., Guzman-Silva, D., Perez-Leija, A., & Szameit, A. (2016). Integrated photonic quantum walks. Journal of Optics, 18(10), 103002. doi:10.1088/2040-8978/18/10/103002

[29] Garisto, D. (2020, December 03). Light-Based Quantum Computer Exceeds Fastest Classical Supercomputers. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/light-based-quantum-computer-exceeds-fastest-classical-supercomputers/

[30] Slussarenko, S., & Pryde, G. J. (2019). Photonic quantum information processing: A concise review. Applied Physics Reviews, 6(4), 041303. doi:10.1063/1.5115814

[31]Wiebe, N., Granade, C., Ferrie, C. & Cory, D. G. Hamiltonian learning and certification using quantum resources. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 190501 (2014).

[32] Chen, Z., & Segev, M. (2021). Highlighting photonics: Looking into the next decade. ELight, 1(1). doi:10.1186/s43593-021-00002-y

[33] Wang, J., Sciarrino, F., Laing, A. et al. Integrated photonic quantum technologies. Nat. Photonics 14, 273–284 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0532-1

[34] Kudyshev, Z. A., Shalaev, V. M., & Boltasseva, A. (2020). Machine Learning for Integrated Quantum Photonics. ACS Photonics, 8(1), 34-46. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00960

[35] Melnikov, A. A., Nautrup, H. P., Krenn, M., Dunjko, V., Tiersch, M., Zeilinger, A., & Briegel, H. J. (2018). Active learning machine learns to create new quantum experiments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(6), 1221-1226. doi:10.1073/pnas.1714936115

[36] Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Rebentrost, P., Wiebe, N., & Lloyd, S. (2017). Quantum machine learning. Nature, 549(7671), 195-202. doi:10.1038/nature23474 [37] Sparrow, C., Martín-López, E., Maraviglia, N. et al. Simulating the vibrational quantum dynamics of molecules using photonics. Nature 557, 660–667 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0152-9